The paper below is a Literature Review exploring the health benefits of volunteering and the effects ICT has on older adults in a volunteering environment (Torrens University, RES611, final assessment). This is the first assessment in undertaking a literature review. Further papers result from this Graduate Diploma of Research Studies.

Introduction

Topic of inquiry

Senior adults are increasingly faced with digital technology in their day-to-day lives. Advances in Information Communication Technology (ICT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, robotics, and other technologies have increased the pace of change tenfold. By 2025, it is estimated that 50 billion devices will be connected to the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) (Kuiken, 2021). Engagement with digital technology is inevitable. The challenge today is how to positively engage senior adults in technology acceptance. The purpose of this review is to identify how countries are addressing senior citizens’ technology acceptance as it interfaces with volunteering environments. Within a framework centered around senior adults, the articles reviewed focus on senior adult learning, seniors’ technology acceptance, senior adult well-being, and volunteering.

Background

Digital exclusion is looming as one of the most problematic issues facing older citizens today (Mubarak & Suomi, 2022). According to the Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII, 2022), digital inclusion among older Australians has increased between 2020 and 2021. Digital inclusion means people can use the internet and technology to improve their daily lives (Good Things Foundation, 2022). However, those aged 65 and over are more digitally excluded than other age groups (Mubarak, 2015). Age is not the only consideration. Factors such as education, income, those living regionally or remotely, fare worse in the digital environment (Neves & Mead, 2021). According to Mubarak and Suomi (2022), the digital divide, when referring to older adults, is known as the grey divide. In this research paper, international literature reveals a divergence in the definition of this grey divide. Mubarak and Nycyk (2017) define the grey divide as those, usually over 65 years of age, who have a problem accessing and using the internet. In their study, the authors further define differences between developing and developed countries. Developing countries are generally characterized by “low to no wages, poor health and education standards, famine, hunger, and a lack of infrastructure” (Mubarak & Nycyk, 2017). A developed country was generalized as having access to better ICT and Internet infrastructure (Mubarak & Suomi, 2022). This literature review will explore the differences between developing and developed nations’ assessment of the digital divide and how this affects senior citizens.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2022), “by 2030, 1 in 6 people in the world will be aged 60 years or over, and between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22%”. “Health is a state of complex physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1952, p.100). Social inclusion enhances the quality of life in older people (Browning & Thomas, 2013). Tsai et al. (2015) suggest that using information and communication technologies can improve older adults’ well-being, quality of life, and social connections.

Social connectedness was one of the health benefits identified by de Wit et al. (2022). These authors carried out studies over 33 years to monitor the effects of volunteering on older adults. Brown et al. (2012) explored the benefits of well-being and volunteering for older adults and found that volunteers reported significantly higher well-being, social connectedness, and general self-efficacy than non-volunteers. Volunteering for seniors is undertaken in diverse social and business environments. Rijmenam (2023) predicts that there will be increasing emphasis on digital literacy in all social environments, compelling a move from basic computer skills expectations to one where all adults will need to be comfortable with advanced AI technologies. This future prediction poses a huge challenge for senior adult ICT learning. This is the area of my research.

Aim of the inquiry

Why is this research so important? With an increasingly aging global population, it is imperative that an understanding is developed around the mechanisms that may improve older adults’ well-being (Francis et al., 2019a). Information and communication technologies are tools that may promote well-being through increased connectedness and reduction of social isolation (Francis et al., 2019b). In a study of 19 assisted and independent living communities, Francis et al. (2019b) identified that ICT engagement promoted social connectedness, creating a sense of self-worth. In later life, senior adults often engage in volunteering to stay connected and relevant today (Jongenelis & Pettigrew, (2020). Volunteering is also identified as being associated with improved physical and cognitive well-being (Jiang, et al., 2020). Yet, Rijmenam (2023) predicts 2023 to be the year of digital disruption. While these predictions are aimed predominantly toward a changing business and economic environment, government agencies need to be mindful that technological innovations will have a significant impact on our societies. The fundamental problem in digital illiteracy occurs when senior adults are unable to keep up with societal trends (such as Generative AI) thus increasing social isolation and reduced self-efficacy (Mizra et al., 2020).

Methodology

Data collection

The current study used international online databases, EBSCOhost, ProQuest, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect for relevant articles. Key search terms included four themes : (1) Digital Divide, Grey Divide, digital literacy, digital competency; (2) older adults, learning; (3) senior adult well-being; and (4) volunteering. The Boolean operators AND / OR were adopted across these searches to capture key search terms such as older adults / elderly / seniors; ICT / digital technology/internet; health/well-being.

Selection of Literature

Following the initial peer-reviewed article collection, 60 studies were selected for maximum relevance to the four themes and then grouped in relevance into the main themes : (1) the digital divide; (2) senior adult learning; (3) senior adults’ well-being; and (4) volunteering and ICT. Most articles demonstrated connections to more than one theme.

Analysis of literature

1. The Digital Divide

The Challenges

The first theme of this research explores how senior adults interface with digitization from various global perspectives. Farooq Mubarak, a Finnish author, has explored the advancement in ICT and the digital divide, comparing the economic and educational influences of developing and developed countries (Mubarak & Nycyk, 2017; Mubarak & Suomi, 2022). He states that multidimensional aspects of the term ‘digital divide’ are complex and affected by cultural complexities (Mubarak, 2015). The meaning of this digital divide in developing countries focuses on public inequality, poor economies, and political and cultural issues that influence the uptake of ICT. Nycyk (2011) identified computer training as a must for older citizens to keep them in contact with society. By 2017, Mubarak and Nycyk (2017) were focusing on the “grey divide”. They identified country type, economic challenges, and cultural beliefs to be considered in understanding the grey divide and the issues that affect older people’s access to internet skills learning. By 2022, Mubarak and Suomi research the social exclusion of the elderly as the use of digital technology has become more prevalent. One of their significant findings was that the grey divide was linked to poor health outcomes in both developed and developing economies (Mubarak & Suomi, 2022). Another interesting finding was observed in developed countries where social exclusion was experienced because of a lack of digital skills. In developing countries, intergenerational family living enabled seniors to receive help from younger family members (Mubarak & Suomi, 2022).

In contrast, a study in Vietnam (Nguyen et al., 2022) identified that 35% of older citizens (60 years and older) had a positive attitude toward the Internet. Due to necessity, senior family members had to earn a living, especially those in rural and ethnic minority households with poor circumstances. In this case, socioeconomic status was proved to positively affect ICT uptake by older people (Nguyen et al., 2022).

Continuing this intergenerational theme, a study undertaken in Ireland explored the digital divide with a focus on younger generational assistance offered to older family members (Flynn, 2022). Identifying that 33% of the population had never accessed the interest, the survey covered social isolation during COVID and social connectedness through family members. Senior adults were identified as “physical natives” as there was a preference for face-to-face interactions (Flynn, 2022). Lockdown experiences stimulated new learning opportunities for digital skills development through their connections with younger family members. For those seniors who did not have family members, there were recommendations for future one-to-one teaching programs (Flynn, 2022). Olsson & Viscovi (2018) identified similar family support mechanisms in Sweden to assist in the digital divide. However, it was stated that elderly Swedes generally had been online for more than a decade yet still sought assistance from “warm experts” (their family members). In a WHO report (2015) there was an identification that only older adults who were more advantaged in society would experience benefits from digital opportunities.

A two-year study in France (Wu et al., 2015) found a link between the digital divide and the motivation for older adults to adopt different kinds of ICTs to fit in with society. Concerning assistive ICTs (for example, robotics, smart home technology, assistive communication devices, and sensors for social alarms), there appeared to be a lack of appreciation of the perceived usefulness of such technologies. Participants in the focus groups stated that the use of these digital devices, “gerontechnologies”, had a negative image for those who used them. However, they rated this overall research study project positively as their inclusion had exposed them to advanced ICTs and societal progress (Wu et al., 2015). While acknowledging the digital divide between older and younger generations, Wu et al.’s focus groups identified security, privacy issues, diminution of human contact, and fear that ICTs may change fundamental human nature (Wu et al., 2015).

The Benefits

Social participation and digital engagement were identified to contribute to health and well-being among older adults (Fischl et al., 2020). It was suggested that digital connectivity led to older adults staying at home longer, a factor that predicted life longevity. WHO report (2015) stated that digital technologies that were tailored to individual needs could enhance older adults’ social participation. This study recognized social participation and digital technology as having the potential to promote health and well-being. Similarly, Marston et al. (2019) identified that developing age-appropriate education strategies would benefit seniors in that they would be able to share information, communicate with friends, enhance social inclusion and interaction, and strengthen intergenerational ties. Wang et al. (2020) explored the impact of digital games, designed for senior adults. While there was limited research literature on this subject, the authors explored the positive health benefits of knowledge acquisition and skills enhancement. In striving to digitally empower older adults, Yoo (2021) discussed the importance of creating a supportive learning environment, which would lead to more productive and enjoyable lives in retirement.

2. Senior Adult Learning: Technology Acceptance

The Challenges

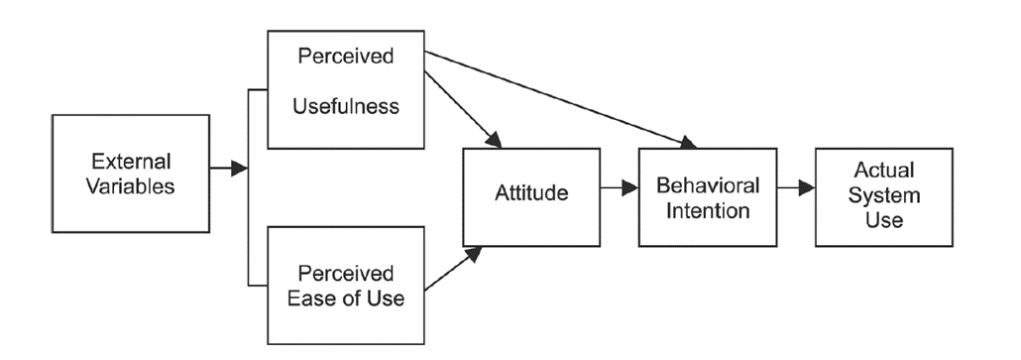

Adult learning has been an age-old preoccupation for academics. In a time when an aging population is inevitable, this second theme explores older adult engagement with technology. There is an abundance of literature exploring the theories of adult learning (Bates, 2016). In 1962, Lev Vygotsky moved beyond behaviorist learning theories to a belief that social interaction and scaffolding helped adult learners to progress to higher levels of understanding (Vygotsky, 1962). While learning theories can predict how an older person can learn new tasks, a more complex dimension appears when reviewing technology acceptance and usage in senior adults (Neves & Mead, 2021). Ghani et al. (2019) explored and modified the four elements of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) framework: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude, and the behavioral intention to use technology, to predict senior adults’ engagement with technology. In refocusing on external variables, the authors were able to define a better understanding of the complexities of senior adult digital acceptance. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Technology Acceptance Model.

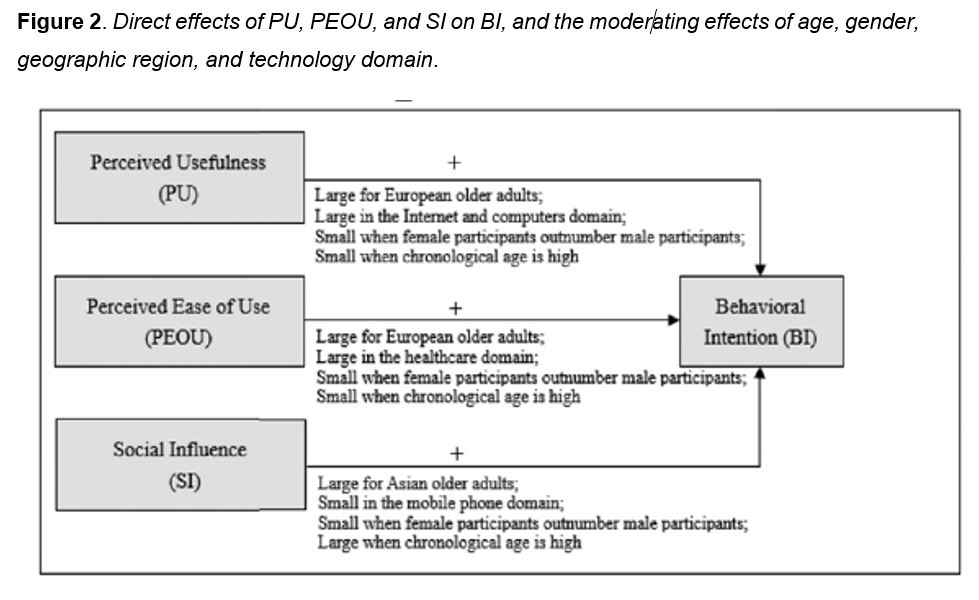

Neves and Mead (2021) identified that senior adults’ adoption of digital technologies was below that of other age groups. This study focused on the 65+ age group and gives a complex exploration of how the elderly approach digital devices. Social context and user contexts of older adults vary from younger generations’ experience and hence, teaching methods need to reflect this difference in both language used and knowledge/experience assumptions (Neves & Mead, 2021). Chen and Lou (2020) explored a version of the Senior Technology Acceptance Model (STAM) creating a questionnaire that consisted of the 4-factor structure, including the technology acceptance constructs (perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude, and behavioral intention) as well as age-related health characteristics. While TAM is a useful model, additional variables need to be understood to answer why there is hesitancy in technology acceptance (Chen & Chan, 2011; Chen & Lou, 2020). These authors identified biophysical decline, selective attention, cognitive ability, and self-efficacy as variables that influence technology usage. Maa et al. (2021) in Hong Kong undertook a study involving 35 primary studies over 15 years to understand the behavioral intention of older adults to adopt the technology. While there were some regional disparities due to cross-cultural differences, it was found that older adults displayed a willingness to accept familiar technologies, such as smartphones, but there was a reluctance in their acceptance of unfamiliar technologies, such as healthcare systems and new devices (Maa et al., 2021). Perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) supported a positive association with behavioral intention (BI). See Figure 2.

Schlomann et al. (2022) and Mubarak and Nycyk (2017) explored adult learning as a linkage to previous experiences, which is termed fluid intelligence. With younger generations being identified as digital natives (Choudhary & Bansal, 2022; Marston et al. 2019; Ball et al. 2019), seniors are tagged as digital immigrants who do not have the fluid knowledge to connect to learning as there are no previous experiences in their skills set. Another factor to influence technology acceptance in seniors has been identified by Ball et al. (2019). Seniors like to connect socially but they feel inadequate when they look at others around them who are better at technology, creating a physical-digital divide. The report states that senior adults like to connect physically (physical natives) while younger generations are identified as digital natives (Ball et al., 2019). Code (2020) discusses agency for adult learning as intentionality, forethought, self-regulation, and self-efficacy. She identified that this agency for learning in older people does not have the same intrinsic and extrinsic motivators as for younger learners. Digital immigrants struggle with agency for learning (AFL) as the learning is set around known goals. Personal agency regulates the processes necessary for learning. ICT and AI are new concepts that are not generally in the knowledge experience of older adults (Code, 2020). An Israeli study of 135 older people was undertaken to assess if the use of unfamiliar technology made them feel older (Capsi et al., 2019). The results were that even when using a relatively common technology on an easy-to-use device, these senior adults still felt older after the experience.

Positive Strategies

In contrast to the authors reviewed thus far, there are many studies that have identified positive strategies that engage senior adults with technology usage (Chohan & Hu, 2022). Based in India, the authors investigated Adult Learning Theories to develop a training model, that introduced an ICT framework for social development. The concept of M-Learning (mobile learning) was to assist senior citizens in acquiring digital skills to improve their quality of life by fully utilizing e-government services and having a sense of connectedness (Chohan & Hu, 2022). Haan et al. (2021), in the Netherlands, identified strategies to facilitate smartphone usage. This study provided findings in Smart Phone and social apps that are potentially transferable for other senior adult learning environments and provided insights into peer-to-peer community learning in a social setting. Both studies reported positive results.

Canadian authors, Jin et al. (2020) undertook a literature review to explore how mobile devices play a role in senior adults’ informal learning, identifying four theoretical frameworks to interpret their research: (a) TAM (Technology Acceptance Model), (b) experiential learning theory, (c) social cognitive theory, and (d) activity theory. Their conclusions were that self-paced learning on mobile devices can be motivated by health-related subjects, while consistent interaction with these devices assists in familiarity and ease of use. Informal learning, which is appropriate to life needs, promotes, and motivates learning. Similar findings were documented in a study undertaken by Yoo (2021), which was an introductory digital course, designed for older adults. The focus of the results of this study highlighted the need for a quality learning environment with supportive teachers. Several authors have explored the need for supportive, peer-to-peer learning, and differentiated teaching methods to assist in the successful delivery of digital competency (Chen & Chan, 2011; Fischl et al., 2020; Gleason & Suen, 2022; Haan et al., 2021; Maa et al., 2021; Marston et al., 2019; Neves & Mead, 2021; Betts et al. 2017; Nycyk, 2011). With social connectivity as a recurring theme, Sen et al. (2020) suggest that the more social connections senior adults experience, via social activities, community-dwelling, mobility, and use of technology, the higher likelihood of enhanced well-being, health, and less evidence of cognitive decline.

3. Well-being of Senior Adults

The third theme of this research intends to show that well-being in older adults is important to society. An aging population is inevitable. Global trends put an emphasis on healthy living and well-being as imperative to society (Sirbu, 2020). She states that participation in social activities encourages a sense of belonging. This social integration facilitates positive psychological states which lead to positive physiological outcomes (Sirbu, 2020). Promoting meaningful social engagement, and improving self-perceptions by recognizing seniors’ contributions, are recommended by Browning and Nicholson (2013). To reduce healthcare costs and maintain individual productivity, health, and well-being of this segment of the population is important and deserves attention (Sirbu, 2020). Social isolation has been shown to significantly increase the risk of premature death and reduce the quality of life (Plunkett, 2021).

Joulain et al. (2019) undertook studies over five years in France to explore how activities, such as sports and informatics, or volunteering and gardening, promoted well-being in older adults. From their surveys, individuals who reported psychological well-being, not only lived longer, but they also led healthier lives than those participants who had lower rates of activity participation (Joulain et al., 2019). These studies highlighted the beneficial effects of social activities on the well-being of aging people. Their investigation detailed self-actualization, creativity, and service to others (volunteering), as being the positive elements of promoting health and well-being in older adults. These results detailed the beneficial influence of social participation, including getting out of the house, meeting other people, and providing a perceived sense of control, and autonomy (Joulain et al., 2019).

Albert Bandura (1925 – 2011) was a Canadian psychologist who explored the influence that individual experiences, the actions of others, and environmental factors had on individual health behaviors (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy is stated to be the belief a person has in their own abilities, specifically their ability to navigate challenges to complete a task successfully (Bandura, 1988). Individual agency is associated with goals, perceived control, self-efficacy, persistence, mastery, autonomy, and self-regulation (Browning & Thomas, 2013; Heckhausen et al., 2018). Older adults, as digital immigrants, struggle with the agency for learning as digital technology is unfamiliar, physical health limitations exist, and biological aging can affect learning motivation and self-regulation (Heckhausen et al. 2018). Technology provides social connectedness, and access to health information and services, essential for senior adults’ well-being (Plunkett, 2021).

In a Victorian study, Brown et al. (2012) found that volunteers reported higher well-being than non-volunteers. This subjective sense of overall personal self-worth included self-esteem, self-efficacy, and social connectedness. The study concluded that self-esteem and social connectedness mediated the relationship between volunteer status and well-being. As adults move from a career to retirement, social participation can contribute to the health and well-being of older adults (Fischl et al., 2020). These authors go on to suggest that societies need to tailor social opportunities and services to promote associations which may lead to senior adults remaining in their homes longer. Hand et el. (2020) identified 3 themes in a study on how older adults shape and enact agency in their neighborhoods: older citizens need to be present and be open to casual social interaction, be able to help others and take community action. Kleiner et al. (2020) explored the Activity Theory of Aging (Havighurst, 1963), proposing that senior adults are most satisfied when they are active and maintain social interactions. Meaningful activities help the elderly to replace past life roles after retirement and assist in maintaining a quality of life (Browning & Thomas, 2013; Kleiner et al., 2020).

Conversely, emotions, such as fear, apprehension, anxiety, and a sense of isolation have been marked as major health and social problems for seniors (Mizra et al., 2020). Mubarak & Suomi (2022) identify the successful or unsuccessful accomplishment of basic tasks, such as banking, booking entertainment tickets, renewing bus tickets, and paying bills, can affect the mental well-being of older adults. E-Health is predicted to dominate healthcare, and this could lead to seniors avoiding ICT engagement due to a lack of skills and connectivity (Mubarak & Suomi, 2022). Activities, such as social events, community-dwelling, mobility, and the use of technology, demonstrate a connection with well-being, enhanced health, and cognition in older adults (Sen et al., 2020). Bandura (2004) states that people can reduce major health risks and live more productive lives through self-management of health habits. It is incumbent on all organizational bodies to take an active interest in enhancing the health and well-being of senior citizens. Access, affordability, and digital skills are crucial to improvements in senior adult lives (Plunkett, 2021).

4. Volunteering and ICT

Senior adults face challenges with the increased penetration of digital technologies into day-to-day life and social environments. Many studies state social connectedness and social activities have a proven benefit to the health and well-being of senior adults (Brown et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2015; deWit et al., 2022; Francis et al., 2019b). Joulain et al. (2019) acknowledged volunteering could be particularly beneficial to health and well-being. Similar statements are noted in Davenport et al., (2021), deWit et al., (2022), Brown et al., (2012), Fischl et al., 2020, Jiang et al., 2020, Jongenelis and Pettigrew, (2020), Kleiner et al., (2020), and Serrat-Graboleda et al., (2021). These authors suggest that health benefits are derived from social interactions and “services to others” (Joulain et al., 2019). In Australia, the National Volunteer Week theme for 2023 is “Volunteering Weaves Us Together”. This campaign highlights the importance of volunteering in the community. There are currently 11,738 volunteering organizations in Australia and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 20 May 2021) census data shows over 3.6 million people undertake some volunteering activity. 30% of those who did voluntary work for welfare or community organizations are aged 65 years and over (Volunteering Australia, 2021). These statistics direct focus on the volunteering environment that seniors are now encountering. Since the pandemic, QR codes are commonplace, online learning management systems (LMS) are emerging to address workplace health and safety compliance issues, and increased use of digital payment systems at retail outlets has been installed in many volunteering environments. Organizations that depend on senior adult participation to support volunteering activities must recognize that the introduction of digital technologies brings discomfort, which threatens the retention of participants (Jongenelis & Pettigrew, 2020).

Technology has impacted the industry through the introduction of volunteer management software. An example of a volunteer management system, Better Impact (Better Impact, 2023), provides comprehensive data management for individual volunteers, from personal details to assigned learning modules. Volunteers are obliged to navigate this technology to complete mandatory WHS learning. Some studies identify that seniors like to connect socially but they feel inadequate when they look at others around them who are good at technology (Ball et al., 2019; Capsi et al., 2019). Another downside of volunteering is discussed by Davenport et al., (2021) related to physical discomfort, physical limitations, fear of breaking or damaging technology, frustration with new concepts, and age stereotypes. These negative aspects emerged in this study through surveying participants who were considering the impact of leaving a volunteering role (Davenport et al., 2019). Very little literature is available to explore the downsides of volunteering and the interface it has with the increasing use of technology.

There is another type of volunteering, Voluntourism (Volunteer World, 2023), and this is carried out in developing countries. It is a form of volunteering activity where generally younger travelers participate in voluntary work, typically for a charity. According to Volunteer World, 2023, this type of volunteering has negative impacts on the communities themselves. Short-term volunteers may lack cultural understanding and language skills, making communicating and forming relationships with community members difficult. This can lead to feelings of isolation and distrust between volunteers and locals. This type of volunteering is not the concern of this current literature study.

Discussion and Synthesis

In this literature review, no negative peer-reviewed literature on volunteering and the interface with ICT was found. It may be that any negative report of volunteering is an anti-social topic. Many organizations need volunteers. 5.8 million Australians or 31 percent of the population volunteer in some capacity (Volunteering Australia, 2021). It is widely recognized that volunteering (helping others) is beneficial (Serrat-Graboleda, et al., 2021). Digital technology is increasing across all industries, and hence into volunteering environments. Specialist blogs identify the cons of technology as “addiction, isolation, cyberbullying, privacy concerns, sleep disruptions, health risks, distraction, social comparison, information overload, loss of jobs, dependence, decreased physical activity, reduced face-to-face interaction, reduced privacy, and social stratification” (Ablison, 2023). These identified effects show little connection with an analysis of volunteering activities.

In the analysis of literature, terms such as the digital/grey divide and digital technology have different definitions in differing contexts. While most authors define their terminology at the commencement of their studies, comparing explored concepts and the outcomes can be complex. As an example, Wu et al. (2017) were concerned with technology adoption among older adults and their negative perceptions of assistive ICTs. These are advanced health technologies to improve the health and well-being of senior citizens. Compare this study with the German study by Schlomann et al. (2022) where senior adults’ acceptance of technology was associated with fluid intelligence, linked with prior life experiences. While these studies demonstrate the complexities of an advanced age of technology, the study contexts are quite different.

Volunteering literature originates in developed countries (Brown et al., 2012 (Australia); Davenport et al., 2021 (UK); deWit et al., 2022 (European); Jiang et al., 2020 (Hongkong); Jongenelis & Pettigrew, 2020 (Australia); Kleiner et al., 2020 (Switzerland); Serrat-Graboleda et al., 2021 (Switzerland). These developed countries have the socio-economic independence to focus on the mental health and well-being of older adults. Social freedom to participate in voluntary activities in the community is an acceptable pursuit in retirement in a developed country. In contrast with the Vietnamese study (Nguyen et al., 2022) where older citizens were under economic pressure to engage with digital technology, senior adults in developed countries have the choice to engage with ICT in their living or volunteering environments.

Two influences are evident across the selected literature. An author’s cultural background is an influencing factor in the approach to their inquiry. And the second factor that needs consideration is the demographic affluence and education in either developing, or developed, countries.

Cultural Background: An author’s outlook may be influenced by his or her cultural background. For example, Wu et al. (2015) documented a French study where focus groups’ response to participating in the study allowed them to express their concerns, stating that this freedom of expression was essential for successful aging. Some of the participants stated that there was social injustice when society members were compelled to use technology to get access to services (Wu et al. 2015). The Israeli study (Capsi et al., 2019) explored how technology made senior adults feel older. These study outcomes demonstrate senior adults expressing autonomy and self-efficacy. Mubarak & Nycyk (2017) highlight the complex problems arising from the type of culture and society when analyzing the digital divide. Understanding the motivating factors of the culture will dictate how best to approach training seniors in digital technology. Further complexity arises from this research as Mubarak and Nycyk (2017) identified that in Australia, for example, as a developed nation, elderly citizens in rural areas, were willing digital users but lacked essential ICT skills due to a lack of teachers.

Developing Countries: The case study in Vietnam indicates that socioeconomic status can affect ICT engagement (Nguyen et al., 2022). Not only were senior adults engaged in earning a living for their families, but in this collectivist society (Hofstede, et al., 2010), the elderly were more active and ready to adapt to the digital society around them. Literature from developing countries focused more on the uptake of digital devices and access to the Internet (Chohan & Hu, 2022). Rajak and Shaw (2021) highlighted the importance of digital health services in an Indian context. These developing economies do not appear to prompt research literature on volunteering and digital literacy.

Developed Countries: Studies in Canada (Marston et al., 2019), the UK (Flynn, 2022), Australia (Jongenelis & Pettigrew, 2020), and the USA (Ball et al., 2019), focus on how digital immigrants (senior adults) reflect on digital natives (younger generation) and social connectedness and well-being. The French and European literature demonstrates a sophisticated analysis of advancing senior adults’ quality of life, including volunteering as a frequent activity in retirement (Browning & Thomas, 2013). Mubarak and Nycyk (2017) identified an urban-rural divide in Australia. However, the high standards of living in developed countries allow seniors to engage in or reject digitization (Capsi et al., 2017). The French study revealed that one participant identified being compelled to use technology as social injustice (Wu et al., 2015).

Summary of Findings

Literature addressing the specific effects of technology in a volunteering environment was unable to be found. Many articles identified the health benefits of volunteering. Several articles identified challenges that senior adults have in embracing technology. Other authors documented successful strategies that engaged seniors in the use of technology, bridging the digital and grey divide. In the synthesis of this literature, the cultural values of developing and developed countries were identified as having an influence on the authors’ research approach. Because of global differences, there was no one solution in addressing how best to coach senior adults in the use of technology. It is identified in some articles that digital acceptance will enhance senior adults’ quality of life. However, a wide range of scenarios indicates that universal acceptance of technology by senior adults faces significant hurdles. To begin to address the problem of a digital divide, future research needs to narrow to one cultural context to define the causal issues. Volunteering can be seen, in developed economies, as a bonus in later life. In developing countries, senior citizen volunteering does not rate as a research topic. Digital skills and the grey divide are a problem that government organizations will need to address in the quality of life, health, and well-being of their aging citizens.

Conclusion

In an Australian context, there needs to be more research on how digital reluctance is affecting volunteering activities. This country has the economic wealth to support many volunteering bodies. It is incumbent on organizations to address the detrimental effects of technology reluctance, security fears, and self-efficacy agitation. Although the interest of this paper is in a volunteering setting, the grey divide is a universal challenge. With an increasingly aging population and the ongoing penetration of technology into all areas of existence, governments and statutory bodies need to invest in strategies that bring effective digital engagement to senior adults. Further research into senior adults’ technology resistance, and how to improve digital engagement, needs to be urgently addressed.

References

Ablison Blog, 2023. https://www.ablison.com/pros-and-cons-of-technology/#cons-of-technology

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021, May 20). Census data shows over 3.6 million people volunteer. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/census-data-shows-over-36-million-people-volunteer .

Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII), 2021). https://www.digitalinclusionindex.org.au/

Ball, C., Francis, J., Huang, K.., Kadylak, T., Cotten, S., & Rikard, R. (2019). The Physical–Digital Divide: Exploring the Social Gap Between Digital Natives and Physical Natives. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 38(8), 1167–1184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817732518

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1988). Self-efficacy conception of anxiety. Anxiety Research, 1, 77-98. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080%2F10615808808248222

Bandura, A. (1999). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. In Roy F. Baumeister’s (Ed.) The self in social psychology (pp. 285-298. Psychology Press.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social Cognitive Theory : An Agentic Perspective. Annual Review Psychology, 52, 1–26

Bandura, A. (2004). Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means, Health Education & Behaviour, 31,143. DOI: 10.1177/1090198104263660

Bates, B. (2016). Learning Theories Simplified. Sage Publishers.

Be Connected. (2022). Every Australian Online. Australian Government. https://beconnected.esafety.gov.au/

Betts, L., Hill, R., & Gardner, S. (2017). “There’s Not Enough Knowledge Out There”: Examining Older Adults’ Perceptions of Digital Technology Use and Digital Inclusion Classes. Journal of Applied Gerontology,38(8)1147-1166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817737621

Better Impact, 2023. https://www.betterimpact.com/

Brown, K., Hoye, R., & Nicholson, M. (2012). Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and social connectedness as mediators of the relationship between volunteering and well-being. Journal of Social Services Research, 38:468–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2012.687706

Browning, C., & Thomas, S. (2013). Enhancing quality of life in older people. Australian Psychological Society, InPsych, 35(1). https://psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2013/february/browning

Capsi, A., Daniel, M., & Kavé, G. (2019). Technology makes older adults feel older. Aging and Mental Health. 23, 8, 1025–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1479834

Chen, K., & Chan, A. (2011). A review of technology acceptance by older adults. Gerontechnology, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2011.10.01.006.00

Chen, K., & Lou, V. (2020). Measuring Senior Technology Acceptance: Development of a Brief, 14-Item Scale. Innovation in Aging, 4(3), 1–12. doi:10.1093/geroni/igaa016

Chohan, S., & Hu, G. (2022). Strengthening digital inclusion through e-government: cohesive ICT training programs to intensify digital competency, Information Technology for Development, 28(1), 16-38, DOI: 10.1080/02681102.2020.1841713

Code, J. (2020). Agency for Learning: Intention, Motivation, Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulation. Frontiers in Education. 5(19). Doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00019

Davenport, B., Newman, A., & Moffatt, S. (2021). The Impact on Older People’s Wellbeing of Leaving Heritage Volunteering and the Challenges of Managing this Process. The Qualitative Report. 26 (2), 334-351. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4499

de Wit, A., Qu., H., & Bekkers, R. (2022). The health advantage of volunteering is larger for older and less healthy volunteers in Europe: a mega-analysis. European Journal of Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00691-5

Fischl, C., Lindelöf, N., Lindgren, H., & Nilsson, I. (2020). Older adults’ perceptions of contexts surrounding their social participation in a digitalized society-an exploration in rural communities in Northern Sweden. European Journal for the Ageing. 11;17(3):281-290.

Doi:10.1007/s10433-020-00558-7.

Francis, J., Ball, C., Kadylak, T., & Cotten, S. (2019a). Aging in the digital age: Conceptualizing technology adoption and digital inequalities. In: Neves BB, Vetere F, eds. Ageing and Digital Technology: Designing and Evaluating Emerging Technologies for Older Adults. pp 35–49.

Francis, J., Rikard, R., Cotten, S, & Kadylak, T. (2019b). Does ICT Use matter? How information and communication technology use affects perceived mattering among a predominantly female sample of older adults residing in retirement communities, Information, Communication & Society, 22:9, 1281-1294, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1417459

Ghani, M., Hamzah, M., Ramli, S., Daud, W., Romli, T., & Mokhtar, N. (2019). A Questionnaire-based Approach on Technology Acceptance Model for Mobile Digital Game-based Learning. Journal of Global Business and Social Entrepreneurship (GBSE), 5(14), 11-21. http://www.gbse.com.my | eISSN : 24621714

Gleason, K., & Suen, J. (2022). Going beyond affordability for digital equity: Closing the “Digital

Divide” through outreach and training programs for older adults. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 70(1), 75-77. doi:10.1111/jgs.17511

Good Things Foundation, Australia. (2022). https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org.au/

Haan, M, Brankaert, R., Kenning, G, & Lu, Y. (2021). Creating a Social Learning Environment for and by Older Adults in the Use and Adoption of Smartphone Technology to Age in Place. Frontiers in Public Health, Healthy Aging and the Community Environment. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.568822

Hand, C., Laliberte-Rudman, D., Huot, S., Pack, R., & Gilliland, J. (2020). Enacting agency: Exploring how older adults shape their neighbourhoods. Ageing and Society, 40(3), 565-583. doi:10.1017/S0144686X18001150

Havighurst, R. (1963). Successful Aging. Processes of aging: Social and psychological perspectives, 1, 299-320.

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2018). Agency and Motivation in Adulthood and Old Age. Annual Review of Psychology. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-psych010418-103043

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organisations. Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill.

Jiang, D., Warner, L., Chong, A., Tianyuan, L., Wolff, J., & Chou, K. (2020). Benefits of volunteering on psychological well-being in older adulthood: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Aging & Mental Health, 25, (4). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13607863.2020.1711862?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Jin, B., Kim, J., & Baumgartner, L. (2020). Informal Learning of Older Adults in Using Mobile Devices:

A Review of the Literature. Adult Education Quarterly, 69(2), 120–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713619834726

Jongenelis, M., & Pettigrew, S. (2020). Aspects of the volunteering experience associated with wellbeing in older adults. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. DOI: 10.1002/hpja.399

Joulain, M., Martinent, G., Taliercio, A., Bailly, N., Ferrand, C., & Gana, K. (2019). Social and leisure activity profiles and well-being among the older adults: a longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(1), 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1394442

Kanižaj, I., & Brites, M. (2022). Digital Literacy of Older People and the Role of Intergenerational Approach in Supporting Their Competencies in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic. In: Gao, Q., Zhou, J. (eds) Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Design, Interaction and Technology Acceptance. HCII 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13330. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05581-2_25

Kleiner, A., Henchoz, Y., Fustinoni, S.,& Seematter-Bagnoud L. (2020). Volunteering transitions and change in quality of life among older adults: A mixed methods research. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 98. https://doi.org/10.1016

Kuiken, S. (2021). Tech at the edge: Trends reshaping the future of IT and business. McKinsey Insights. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/tech-at-the-edge-trends-reshaping-the-future-of-it-and-business

Maa, Q., Chan, A., & Teh, P. Insights into Older Adults’ Technology Acceptance through Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 37(11) 1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1865005

Marston, H., Genoe, R., Freeman, S., Kulczycki, C., & Musselwhite, C. (2019). Older Adults’ Perceptions of ICT: Main Findings from the Technology in Later Life (TILL) National Library of Medicine, National Centre for Biotechnology Information, 4;7(3), 86. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7030086.

Mirza, R., Sinha, S., Austen, A., Liu, A., Ivey, J., Kuah, M., McDonald, L., & Hsieh J.(2020) Best

Practices and Policies for Addressing Social Isolation Among Older Adults. Innovation in Aging, 16;4 (Suppl 1):319. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igaa057.1020. PMCID: PMC7741401.

Mubarak, F. (2015). Towards a renewed understanding of the complex nerves of the digital divide. Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 71–102. DOI: http://doi.org/10.36251/josi.93

Mubarak, F., & Nycyk, M. (2017). Teaching older people internet skills to minimize grey digital divides: Developed and developing countries in focus. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society,15(2). https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-06-2016-0022

Mubarak, F., & Suomi, R. (2022). Elderly Forgotten? Digital Exclusion in the Information Age and the Rising Grey Digital Divide. The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 59, 1-7. DOI: 10.1177/00469580221096272

Neves, B., & Mead, G. (2021). Digital Technology and Older People: Towards a Sociological Approach to Technology Adoption in Later Life. Sociology, 55(5), 888–905. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520975587

Nguyen, T., Tran, T., Dao, T., Barysheva, G., Nguyen, C., Nguyen, A., & Lam, T. (2022). Elderly

People’s Adaptation to the Evolving Digital Society: A Case Study in Vietnam. Social Sciences, 11(8), 324. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080324

Nycyk, M. (2011). Older adults and the digital divide: community training to increase democratic participation. ResearchGate Publications. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43511436_Older_adults_and_the_digital_divide_co mmunity_training_to_increase_democratic_participation

Plunkett, L. (2021). It’s Time to Address Broadband Connectivity Issues for Older Adults. Centre for Healthy Aging for Professionals (National Council On Aging NCOA) https://www.ncoa.org/article/its-time-to-address-broadband-connectivity-issues-for-olderadults

Rajak, M., & Shaw, K. (2021). An extension of technology acceptance model for mHealth user adoption. Technology in Society, 67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101800

Rijmenam, M. (2022). What is the future of Artificial Intelligence? The Digital Speaker. https://www.thedigitalspeaker.com/content/files/2023/01/10-Technology-Trends-2023.pdf?Email=tracy.walker%40education.torrens.edu.au&Name=

Schlomann A., Even, C., & Hammann, T. (2022). How Older Adults Learn ICT—Guided and SelfRegulated Learning in Individuals With and Without Disabilities. Frontiers in Computer Science. 3, article 803740. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2021.803740

Sen, K., Prybutok, V., & Prybutok, G. (2020). Determinants of social inclusion and their effect on the wellbeing of older adults. Innovative Aging. 4(1) 319-319.

Serrat-Graboleda, E., González-Carrasco, M., Casas-Aznar, F., Malo-Cerrato, S., Cámara-Liebana, D., & Roqueta-Vall-Llosera, M. (2021). Factors Favoring and Hindering Volunteering by Older Adults and Their Relationship with Subjective Well-Being: A Mixed-Method Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6704. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136704

Sirbu, A. (2022).On the Importance to Study Older Adults Well-being. Journal of Public Administration, Finance and Law, 23. https://doi.org/10.47743/jopafl-2022-23-20

Tsai, S., Shillar, R., Cotton, S., Winstead, V., & Yost, E. (2015). Getting Grandma Online: Are Tablets the Answer for Increasing Digital Inclusion for Older Adults in the U.S.? Educational Gerontology, 41(10). https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1048165

Volunteering Australia. Key Volunteering Statistics January 2021. https://www.volunteeringaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/VA-Key-Statistics_2020.01.pdf

Volunteer World, 2023. https://www.volunteerworld.com/en/volunteer-abroad/voluntourism

Vygotsky, L. (1962). Thought and Language. MIT Press.

Wang, Y., Hou, H., & Tsai, C. (2020). A systematic literature review of the impacts of digital games designed for older adults. Educational Gerontology, 46(1) 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1694448

World Health Organization. (1952). Constitution of the World Health Organization. In World Health Organization handbook of basic documents (5th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2013/february/browning

World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. WHO Press.

Wu, Y., Damness, S., Kerherve, H., Ware, C., & Rigaud, A. (2015). Bridging the digital divide in older adults: a study from an initiative to inform older adults about new technologies. Clinical Interventions on Aging. 10, 193-200. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S72399

Yoo, H. (2021). Empowering Older Adults: Improving Senior Digital Literacy. Auburn University. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611612.pdf